How Corruption Ruins Our World

Note

Originally published on January 14, 2022 on Medium, now updated and hosted here.

Do not pervert justice or show partiality. Do not accept a bribe, for a bribe blinds the eyes of the wise and twists the words of the innocent.

— Deuteronomy 16:19 (New International Version)

Introduction

My name is Eron Lloyd. I was born and raised in Reading, Pennsylvania, and I spent the majority of my life living in and working to improve my hometown. On November 30th, 2015, I plead guilty to one count of Conspiracy to Commit Bribery in Federal court, and became a felon for my actions as a public official of the City of Reading.

Having my career and much of my life’s work end this way was a heartbreaking and personally devastating experience for me and my family. It was a shock to the many friends and allies I worked closely with on nearly a decade of efforts, and signaled the end of what I hoped to be a lifetime of public service continuing the work I started in the city.

It’s now been nine years since that happened and, despite the hardship I experienced, I believe I’m a much better person having gone through what I did. It was the most costly education I’ve ever paid for, but I would not give up what I’ve learned to go back in time and avoid it. I’ve stayed relatively silent for the first six years while I pieced my life back together, but I’m ready to share my story.

This essay is structured in four parts:

- Part 1 is my recollection my downfall. If you know or heard of me, and wondered what happened since city hall, I start there.

- Part 2 goes into my background, beginning with my youth, and traces the path that lead me into public service.

- Part 3 explores my time in city hall, covering key events that I believe contributed to the decline and fall of the Spencer administration.

- Part 4 attempts to cover what I believe we need to do to address the root causes of corruption, beginning within our politics.

Before I begin, I believe it’s important to state up front that I want to share my experience as objectively as possible without blaming or shaming anyone else involved, and any criticism is directed not at the individuals involved but part of the larger problems behind what happened. I fully accepted responsibility for my actions and the consequences that followed, I deeply regret my personal failures along my journey, and I am working toward redemption every single day.

I’ve also forgiven all those who transgressed against me during this period, and ask for forgiveness to the many people I hurt and failed along the way, too. I’ve since learned of the multiple personal weaknesses I had during this time, as well as the larger systemic issues that influenced everything that happened, and these are the areas I’ve decided to focus my energy on changing. If you know corruption must end and want a TL;DR shortcut to my perspective on what must be done, please jump to Part 4.

I’m not here to make excuses for myself or anyone else involved. If nothing else, may my experience be a lesson for those that now walk the same path that I did, and may they avoid the pitfalls along the way. More than sharing a cautionary tale, however, my ambition is to contribute towards fixing the problems at the core of corruption.

Corruption is not just human nature, although ego and arrogance certainly fuel it. It’s a systemic failure of policies and institutions that can destroy our most altruistic efforts to improve human life, such as deepening democracy, expanding economic opportunities and infrastructure, and even protecting the planet.

Essentially, if allowed to exist, corruption can and will hijack a society’s most important functions within government, religion, business, and beyond, and redirect society’s collective goals to a singular goal of the concentration of money and power. It’s a simple yet terrifying fact.

Corruption is often compared to a cancer, but that may not be an accurate analogy. Perhaps a virus is more accurate, because I believe it can spread from person to person with just an exchange of cash. Whatever disease you want to compare it to, it appears as an infection that we continually attempt to remove when it’s detected.

But like John Snow and the Broad Street pump, if we continue to treat the symptoms, and not the cause, the most important goals of society will continue to become terminally ill and die. From my hard-earned perspective and experience, we’re a lot closer to that point than most people realize.

I appreciate your interest in my story. Let’s get started.

PART 1: Beginning at the End

This story begins on the morning of July 7th, 2015, essentially the end of my career in public service. I was in a meeting outside of city hall when I was visited by FBI agents, who began questioning me about a corruption investigation centered around my boss, Vaughn Spencer, the then mayor of the City of Reading. Their last words to me were that I “should get a lawyer.”

I was stunned at the reality I now faced. Within days my world felt like it was crashing down around me, and I watched with grief and fear as my career and all the work I had done to date began to fall apart under the weight of my legal situation. “How did I get here?” was the question that cycled through my mind every day as I looked back at the path that I still thought I had been on the entire time.

In a Legal Free Fall

No one ever realizes what a conspiracy is until you’re considered part of one under the law; it is not a position you want to be in. Within a week of that first visit with the FBI, I began cooperating with the investigation. In the weeks and months that followed, I entered a surreal period of trying to navigate a storm without crashing on the rocks that surrounded me.

On November 30th, 2015, I faced the most difficult day of my life: I pleaded guilty to a single count of conspiracy to bribery. The Hon. Juan R. Sánchez, Chief Judge for the Eastern PA District, was the judge presiding over the entire case, and I stood before the man that would be making the decisions over my fate with incredible trepidation.

The hearing was essentially procedural in nature. The charges against me were defined in a guilty plea memorandum, and I was there to essentially agree to the offenses described and commit to cooperating with the prosecution for the duration of the trial. For questions related to each offense, I responded with a simple “Yes, Your Honor” as the judge read through the memo and noted each response for the court record.

I remember after that the judge paused, looked at me with a puzzled expression, and inquired as to why a person of my apparent character and achievements, with no prior issue with the Law, was involved in this case. I wasn’t truly prepared to answer that question, even to myself. “I’m going to need you to explain that to me,” he continued, and my attorney signaled to me to just acknowledge his statement and remain silent.

I shook hands with the prosecution, was escorted downstairs to have my photos and fingerprints recorded, and then walked out of the courthouse with a criminal record, entering an uncharted area I never expected my life would take me. “Where do I go from here?” was the only question going through my mind.

Landing on My Feet

I was told early on by my attorney, Shaka Johnson (with no relation to Mayor Spencer’s attorney, Geoff Johnson), that court processes for cases like this are often very slow and may take years until trial, so I maximized my time as much as possible. His office and the U.S. Court system Pre-Trial Services staff were very supportive during this supervisory period, and I am very grateful for that.

I was determined to stabilize my life and stay positive and productive while waiting for the trial and my subsequent sentencing. Despite having spent nearly all of my professional life in public service, I accepted the fact that my career there was over and, feeling awash with shame, I wanted to just lay low in general. But I needed work, and I needed anything else that would take my mind off what was happening to me. I would need to reinvent myself again.

Tapping my passion for analytical thinking and technology, I decided to pursue a Masters degree in Data Science, and by December 31, 2015, I was accepted at Lewis University as a full-time graduate student. Further leveraging my technical and analytical skills, I was recruited to work as a business analyst for a local telecommunications service provider in the Spring of 2016.

In addition to now having a steady income and educational goals, I was able to finally concentrate on decompressing and detoxifying all the stress that was slowly eating me alive. With the support of my psychologist, I spent time each week unraveling and untangling my mind in pursuit of answering the “how did I get here” and “where do I go from here” questions.

As my questions got deeper, I tapped into my dormant spiritual side. Buddhism had resonated with me for a long time, and I definitely was awakening to my suffering, so I decided to explore what it could offer my personal work of healing and growth. I stumbled across the Dharmapunx NYC, and found a spiritual home. The book Unsubscribe, by Josh Korda, helped to ground my efforts to understand myself and my faults.

Along with the love and support of my incredibly supportive family and friends, all this gave me the strength and determination to remind me of who I am and that my failures do not define me. I cannot thank everyone that’s been there for me enough, and hope I can continue passing that loving-kindness energy through to those who need me, too.

Facing the Past

On July 26, 2017, Mayor Spencer was charged with bribery, honest services wire fraud, and conspiracy. At his plea hearing, he pleaded not guilty. My heart sank, knowing this was going to trial.

It took a long time to get to the trial of Mayor Spencer, where I would be needed to testify as a witness for the prosecution. I’d get notices of a change in date, anxieties would flood my mind and I’d clear my calendar in preparation, only to have it postponed again. On August 27th, 2018, however, that day finally came. To give some context, I graduated with my M.S. in Data Science from Lewis University just the day before. It had been nearly three years since my plea hearing, and I was more than ready.

All court activities took place in Philadelphia. About a year before the FBI raid, I remembered visiting an adjacent federal building to talk with officials there about sustainability. It’s remarkable to think about how time and circumstances can shift your experiences in the very same location. Entering the courthouse with my family and my legal team, we were escorted to a waiting room for witnesses. I was told that one of Spencer’s campaign consultants was on the stand, and inside were his belongings, including his cell phone.

Seeing his phone, I was immediately flooded with memories of his incessant, exhausting phone calls and texts, pressuring me to do things I didn’t want to. Most of the time I could ignore him, and I did my best to avoid him, but obviously that strategy failed in the end. Four years ago, I would have been enraged with even the sight of his belongings, much less being within 100 ft. of him, but I maintained my composure, focused on my breath, and focused on what I was there to do.

To me, this consultant embodied someone with a great deal of suffering, visible in the way he thought, spoke, and acted. In the end, he was still a teacher, and through our interactions and the consequences that followed, I learned important lessons about myself, as well as how to better deal with a person like him. I hope he’s found peace and a better path through life having been given a second chance.

When it was my turn to appear on the stand, I looked out across the courtroom as I sat down. My eyes went first to my family, and then to the defense table, where I saw Vaughn Spencer for the first time in over four years. I believed he and I developed a strong bond through the many highs and lows of our time working together, but after years of reflection I’ve come to the conclusion that it wasn’t a healthy relationship. I should have stepped down from my position and left the administration a long time ago. If I had, I probably wouldn’t have been sitting where I was that day. I’ll talk more about that later.

I shifted my eyes away from Spencer and then to the jury box. While my fate remained directly with the judge, these jurors would be the ones to ultimately rule on Spencer’s fate. My duty was to honestly and openly recollect what happened for their benefit. I then looked at the prosecution’s table and awaited their questions.

My time on the stand felt like forever, but I maintained a sense of calm and control. I answered all questions asked by both the prosecution and defense as best I could, tapping memories of people, places, and events I had been suppressing this entire time. I was questioned for roughly five hours, including a lunch break in-between. My main hope was to only have to do this once; returning to the witness stand because the trial ran out of time that day was not something I wanted to face.

Fortunately, my testimony covered everything to both sides’ satisfaction that day. Relieved, I returned home happy with my handling of the third most difficult day of my life (the second was yet to come). I’m not going to recount all the details of the trial that day, but you can read here and also here for good summaries from some of the journalists that were present.

Facing the Future

On April 1, 2019, the second hardest day of my life arrived: my sentencing hearing, where the judge would decide my final penalty for my offenses, taking into consideration both the prosecution’s recommendations and the defense’s allocution statement. Returning to the courthouse this time were my family and I, my attorneys, as well as a group of some of my closest friends and nearly all my colleagues from work. I was prepared for the worst, but still hoped for the best outcome.

Appearing before the Hon. Chief Justice Juan R. Sánchez again, I stood up and began reading my allocution statement. I felt I was thoroughly prepared and my statement was good enough to read out loud in court, but I don’t think it’s good enough to share as-is publicly. Instead, I decided to use it as the basis for this entire piece, and it contributed to the content in many ways.

While reading it, and with the judge listening intently, my attorney quietly signaled me to wrap it up, even though I was barely through half of the carefully worded statements. Confused, I trailed off in my statements and thanked the court for the chance to speak. Shaka Johnson looked at me reassuringly, and we sat down as the prosecutors prepared to speak next.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Michelle Morgan, speaking on behalf of the federal government, gave several brief statements recognizing the extent of my cooperation with the prosecution, and asked for a significant downward departure from what the Federal Sentencing Guidelines determine when calculating an offender’s punishment.

I was caught off guard, as the prosecution seemed to be recommending the exact reduced sentence we’d been hoping for, which I read was uncommon. I looked at Shaka to get confirmation, to which he smiled knowingly, and I then realized why he shortened my allocution statement. And with that, the judge accepted the downward departure and sentenced me to six months of house arrest, a $7,600 fine, and five years of probation.

I thanked the court and prosecution, hugged everyone with relief in my party, and returned home knowing that the worst was finally over. Throughout my ordeal, I was never in handcuffs, and never placed in a prison cell. As difficult as it was to endure the entire process, it could have been much, much worse.

Six months later, I was authorized to cut off my ankle bracelet, began visiting people and places I’d missed, and was even able to still make my annual silent retreat organized by Dharmapunx NYC in the beautiful Hudson River Valley in upstate NY. Besides my remaining time on probation, my sentence is now behind me and I’m otherwise thriving better than I ever did while working for the City.

Today I can safely look back on what happened with wisdom and humility, and look forward with courage and confidence knowing that I am firmly rooted and ready for the future. But for now, let’s travel back to where it all started, and take a closer look at who I am and how the city helped shape me, as an important backdrop to the story.

PART 2: Reading Born and Raised, and Bound to Be Political

I was born and raised in the City of Reading, now the forth largest city in Pennsylvania, and lived in a neighborhood in the Northwest part of town. The oldest of two children in a mixed-race, working class family, life wasn’t easy, but I grew up in a stable, loving, and close-knit familial structure.

I attended the Reading School District from pre-kindergarden through high school, and my favorite places to go on my free time were the parks, local swimming pools, and the Northwest and Main branches of the Reading Public Library. In nearly every way I’m a proud product of life in the City of Reading.

An Early Start in Civic Engagement

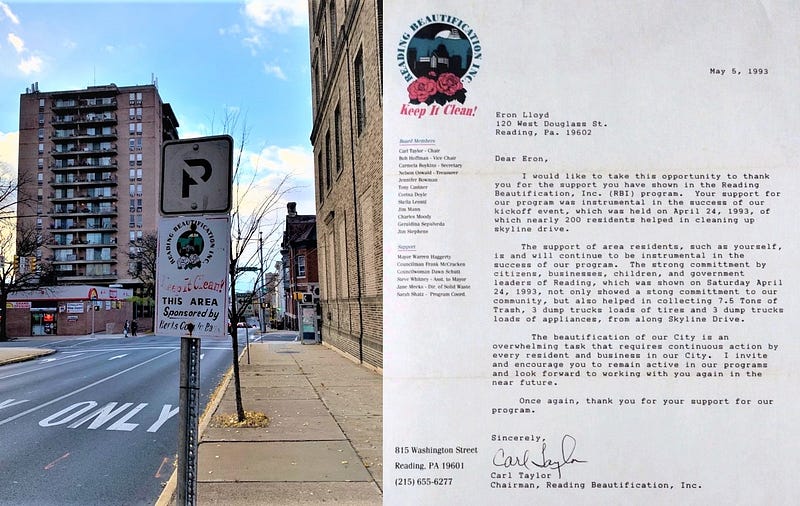

My first memorable experience with civics was in eighth grade, while I was at Northwest Middle School. The City announced an art contest for the logo of a new anti-littering initiative named Reading Beautification, and the schools encouraged students to submit ideas. I enjoyed drawing, and decided to participate, and was selected as the winning entry.

That Spring, the winner was announced during Reading’s annual Earth Day celebration, and I was invited to accept an award presented by Mayor Warren Haggerty at the bandshell in City Park. He asked me to speak, and I went on some rambling lecture about littering, but after that I felt proud to see my logo throughout the city on signposts. A seed of civic duty and impact was implanted in me.

I soon became rooted in public service and municipal government as a teenager. Starting in 1994, I spent my summers as a lifeguard at Schlegel Park pool, which is a public pool managed by the City’s then Bureau of Recreation, which made me a City employee. Throughout these early years I enjoyed public service as a City employee, each summer working to improve the pool for both the patrons and staff.

After generally struggling to find my identify and fit in while in 9th and 10th grade, I continued my course to become more civic minded while in high school. I spent my junior and senior years in Knight Life, RHS’s audio/visual club, and enjoyed operating equipment behind the camera. I also had the privilege of getting in front of the camera regularly as a panelist on a joint venture between RHS and Berks Community Television (BCTV) entitled “Bridging the Generation Gap,” a show that engaged students with adults on a variety of hot topics.

I still rambled at times, but became increasingly more aware of social issues while finding my voice and the confidence to speak about them. It was one of my favorite activities during those years. I’d like to thank Pastor Luther Routte and the other adults on the panel that would listen to us students and engage with our options and ideas. It was very encouraging for me to know that there were adults that valued my input.

I got to know BCTV’s director, Ann Sheehan, and became directly involved with BCTV when I started volunteering at their Internet Kiosk, where people could sign up to access the Web and have someone help them navigate this new experience. Around this time I myself got the privilege of accessing the Internet from home, and was eager to share what I was learning with others.

While volunteering at BCTV I met Tom McMahon (who later would become mayor) and learned about a newly organized effort called the Berks Coalition for a Healthy Community (BCHC), an ambitious effort led by the Reading Hospital to bring together leaders from across the county as stakeholders working towards a shared vision.

Fueling that vision was the Berks County Pierce Report, authored by Neil R. Pierce and Curtis W. Johnson, which weaved the county’s past and future together, asking stakeholders to envision where Reading and Berks County will be in a decade. This report resonated with me, and would shape my own future efforts, which I’ll discuss further below.

I joined the BCHC and was recruited as a leader of the Youth Action Team, attending monthly meetings and even traveling to other areas for events. Through my time involved in BCHC, I was introduced to a number of influential community building concepts, particularly Kruger and McKnight’s Asset-based Community Development (ABCD) model and related community indicator models. Reading suffered from a very negative reputation, which began to frustrate me the more I heard about it, and these approaches offered a new lens to viewing my community for its potential.

The BCHC effort seemed to dissipate toward the end of my time in high school, and I began focusing more on what I planned to do after graduation, but I held onto that passion for community change. When I graduated from Reading High School (RHS) in 1998, I spent my last summer at Schlegel Park as pool manager. Less than a year later, I was hired by the Reading Public Library — another City function — as the part-time webmaster/IT support person. My job at the Reading Public Library then helped me land a full-time IT position with the Lancaster County Library. This allowed me to move to Lancaster and be close to Sarah, my then-girlfriend, and now-wife, while she started college at Millersville University.

Growing Up and Moving Out

From 2001 to 2005 I lived outside of Berks County as I began my own life. The 2000 election and 9/11 both had a profound impact on my life, and I quickly became a community activist while living in Lancaster City. I protested the Iraq War, participated in Neighborhood Watch, and became a disability rights advocate. Through all these activities, I increasingly realized the role politics plays in all outcomes; that “community building” was just not enough. Electoral political became my focus.

I learned of the Green Party from Ralph Nader’s 2000 Election campaign and the “spoiler effect” debate that followed, and through my anti-war efforts I joined the local Green Party after realizing their values most closely matched my own. I became a political organizer, campaign manager, and party leader. Despite my efforts, we got nowhere. It felt like the system was rigged against us, and as I learned about the true nature of third parties in U.S. politics, and elections in general, I realized I was right.

In parallel with my work with the Green Party, I had been using my technical skills to try and fix the issues with the election machines involved in the 2000 Election. After reading Black Box Voting, I joined the Open Voting Consortium (OVC), as a founding member and core developer of their innovative open source election machine that produced voter-verifiable paper ballots. Team members were encouraged to perform demos of the system across the country, so I held one at the Lancaster County Library. Like my work with the Green Party, however, our system never got the traction and attention it deserved.

Through my frustrations as a political activist, I decided to further concentrate my efforts on political reform; simply “running for office” and “getting out the vote” is not enough. I grew disenchanted with technocratic solutions and believed more fundamental institutional reforms were the only answer. I planned to go back to school and study political science. I learned about electoral systems, such as proportional representation and instant runoff voting, and wanted to dig deep into these ideas.

When Sarah graduated from Millersville University in the Spring of 2004, we got married and prepared to move to Massachusetts for her graduate work at UMass Amherst. On our honeymoon, my wonderful wife even allowed me to attend a voting symposium at Harvard University while we were looking for apartments. I started studying at Holyoke Community College and getting involved in political activities both on and off campus. One of my favorite authors on political reform, Douglas Amy, lived in the same community I did, and I had the privilege of sitting down with him and picking his brain. I felt I was right where I needed to be.

Returning Home and Reinventing Reading

Plans often change, however, and Sarah and I decided to return home to be closer to our families after only six months in Massachusetts. Sarah began working at Berks Women in Crisis (now Safe Berks) while I continued my general studies at Reading Area Community College (RACC). We were committed to living in the city, and decided to buy a home. I learned about the Our City Reading organization, which rehabilitated blighted properties for first-time home buyers, so we entered the program and bought our first home. It was a very exciting moment.

After returning home, however, I quickly grew disappointed in the state of the city. Conditions continued to decline, especially in the downtown, and the overall health of Reading displayed red flags on nearly every indicator. This was not the way it was supposed to be based on the vision in the 1996 Pierce Report. Living in Lancaster City, I saw a slow but steady improvement while I was there. Reading appeared to be going in the opposite direction.

While working on my formal studies, I decided to pursue independent research into why my hometown continued to decline despite the many efforts of those before and after me to this point. I analyzed every article I could find in the Reading Eagle, spending most of my days in the libraries searching for answers to everything from low voter turnout to declining municipal revenue. I dreamed of writing a follow-up to the Pierce Report, factoring in the city’s new reality as well as innovative ideas that could help.

After researching and writing for a few months, I realized I’d been compiling enough material to produce a full report, and I envisioned publishing this information in an accessible way for Reading’s civic leaders to use as a reference guide for tackling the city’s challenges. In the Spring of 2006, I released my document, entitled Reinventing Reading: A Comprehensive Vision and Framework for Revitalization, and made it freely available online. In it’s final form, it was more like a book at nearly 150 pages, with a table of contents, index, and appendices. I was obviously quite proud of myself for accomplishing this.

I hand delivered a hard copy to Mayor Tom McMahon, and invited city council and others to a public presentation at RACC where I summarized my recommendations. Sadly it never really had the impact I envisioned. I was 26 at the time, and though many people were familiar with me, I never really engaged with anyone while writing it. I just sequestered myself with my research materials and PC for over a year like I was on a sabbatical while I wrote. At the time I believed I was just trying to help, but no one asked for another dense report, and some were skeptical of my agenda. I definitely may have appeared a bit pretentious, looking back.

Nevertheless, my work had a profound impact on my own life. It affirmed my love for research and writing, especially on public policy topics. I also believed that economics might be a good fit for me, as so much of public policy seemed to be tied up around either how policies would be funded or affect the economy. Seeing how economics seemed to be the biggest challenge facing Reading, I turned my attention to that next.

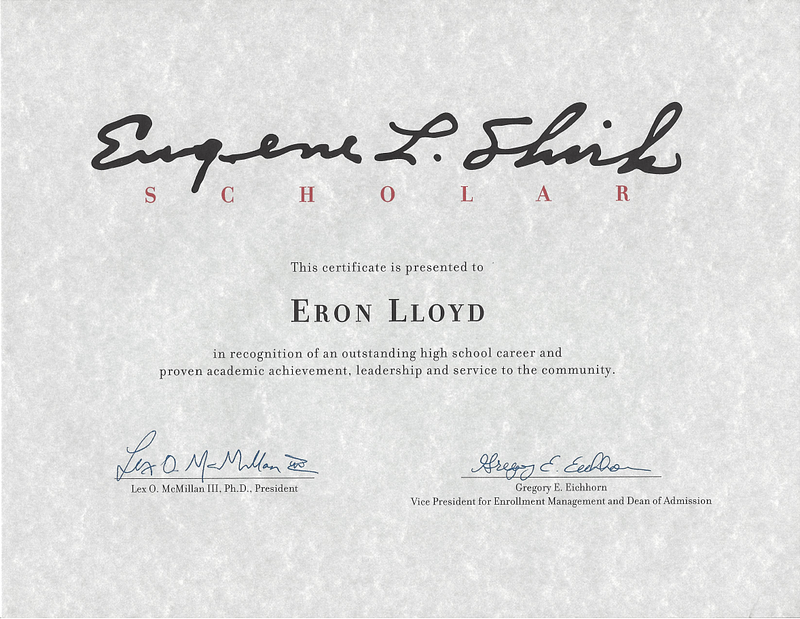

After releasing Reinventing Reading, I was also wrapping up my Associate’s degree at RACC, and deciding where to transfer to pursue my Bachelor’s in Economics. I wanted to continue studying locally, and Albright College looked like a good option, but I couldn’t afford the tuition. While reviewing the enrollment process, I learned about the Eugene Shirk Scholarship, which would cover most of my costs each year, and was told that RACC students qualified. Eugene Shirk was a professor at Albright, a former mayor of the city, and even president of BCTV. I thought everything about that was awesome, and I immediately applied to Albright as well as for the scholarship, and got accepted and awarded the funding.

I started classes at Albright in the Fall of 2006, and spent most of my time for the next year on my coursework, my part-time job, and working on our new home. During that time, however, I also became very interested in the Georgist school of economic thought, best known for the land value tax policy, and began collaborating with the Center for the Study of Economics in Philadelphia. In the Summer of 2007, I did an internship there as a economic policy analyst, and became quite passionate about the mission of the organization. That Fall, I started working part-time for the organization while I finished my degree.

Rebuilding and Recovering Reading

Sarah began planning to return to school in 2008, and got accepted into Temple University’s Doctoral program in Sociology starting that Fall. We moved down to Philadelphia in late Summer, and I began working full-time at the Center for the Study of Economics. Our focus was working with cities large and small on tax reform and public finance, and I got exposed to the political cultures of Manhattan Borough, Philadelphia, and other prospective places that we worked with. I found the work challenging but enjoyed the fast pace in that environment. At this point I felt that my time in Reading was probably complete; while I loved the idea of focusing on the local level, I’d continue to advance policy at a larger scale. But things do have a way of coming full circle.

In the Summer of 2009, I was contacted by Charles Corbett, who was serving on a blue ribbon panel created by Mayor McMahon to review the City’s fiscal health, which had been steadily declining. Part of their charge was to determine whether the City should enter Act 47. Officially named the Municipalities Financial Recovery Act, Act 47 is designed to give financially distressed municipalities specific resources and powers to help avoid bankruptcy and gradually stabilize their fiscal health.

Entering Act 47 includes many significant ramifications, including state oversight requirements, new tax revenue capabilities, and dramatic spending cuts to municipal operations. Charles asked the Center for the Study of Economics to speak to the panel about the land value tax and other revenue options to help stabilize the City budget without discouraging economic development. It was at this meeting that I met Lawrence Murin, a retired Labor leader and member of the panel, and whom I would continue to work closely with while at city hall.

On October 6, 2009, I received an email from Stephen Glassman, Chair of the PA Human Relations Council, who requested my participation in a new initiative being launched by Mayor Tom McMahon. Recent Census data indicated Reading was now the sixth-poorest city in the nation, and the City wanted a community-led effort to identify ideas to combat the decline.

I met with the mayor and other invitees the next day, and agreed to assist the newly-formed Rebuilding Reading Poverty Commission as its economic policy advisor, working closely with Glassman and Jane Palmer to guide the effort. The Commission spent the next year and a half holding hearings and working through its subcommittees to develop its recommendations, which were approved by both the mayor and city council and released as the Rebuilding Reading Poverty Report on March 19, 2011.

In November, 2009, following the submission and review of the blue ribbon panel, Mayor McMahon initiated actions to enter the city into the Act 47 program. In response to the announcement, a large group of community leaders, including Council President Vaughn Spencer, Lawrence Murin, and other members of the previous blue ribbon panel, convened a meeting to decide how to ensure it had a voice in the process as a state-assigned oversight team was established and began holding local meetings to collect input.

I was invited back as a representative of the Center for the Study of Economics for that initial meeting, and the group decided to organize into a grassroots initiative to provide input into the Act 47 plan. Shortly after that meeting, I parted ways with the Center for the Study of Economics, but stayed on as an independent member of the newly formed Act 47 Community Committee, and I would spend my time finishing my Bachelor’s of Economics from Albright and traveling back and forth from Philadelphia to Reading to support both the poverty commission and community committee.

Another Journey Back Home

In the Spring of 2010, Sarah and I decided to again move back to Reading, as her graduate coursework was winding down and with all my energies devoted to Reading, it made little sense to remain in Philadelphia. In the weeks before we left, I attended a conference on composting (a strong personal interest of mine), which headlined Will Allen of Growing Power, who I was eager to hear speak. His story was so much more inspiring than I expected, and while waiting to meet him, I ran into two good friends of mine from Reading, Neil Brantley (now known as Ijendu Obasi) and Brian Twyman, and was introduced to Alexis Campbell.

The three of them were there to also hear Allen speak, but also were exploring ways to collaborate on garden-based community development back in Reading. Ijendu had done incredible community gardens in the city, often with few resources, and Brian and Alexis also shared the same passion. Having already wanted some hands-on work in sustainability efforts in addition to my policy work, I agreed to help them set up a non-profit focused on permaculture education. Shortly after that, Permacultivate was born.

Motivated by the possibilities presented by Will Allen, we quickly set about acquiring resources and space in the city to begin our operation. Unfortunately Ijendu transitioned to another job outside of Reading, but we were able to recruit another good friend of mine and fellow permaculture expert, Phil Wert, as well as Lori Kaplan, who was also active in the gardening community in the city, to our board.

Within a single year, our team secured the rights to use the vacant municipal greenhouse in City Park courtesy of Mayor McMahon, a 2.5 acre vacant lot near Canal St courtesy of the Reading Redevelopment Authority, and community garden plots courtesy of Berks Nature. We then started creating additional projects across the city, including an aquaponics station at the Millmont Elementary School and a garden sanctuary in a courtyard at Reading High School.

In the Spring of 2011, I volunteered as a policy advisor to mayoral candidate Vaughn Spencer through his successful primary win, polishing work done by the Act 47 Community Committee during the campaign trail. In addition to Permacultivate, I also led the creation of the Sustainable Berks Business Network, modeled on the Sustainable Business Network of Philadelphia, which became a program of the New Creations Community Development Corporation, a Reading-based nonprofit. That year, I was also appointed by Reading City Council to the Reading Area Water Authority, and subsequently served as vice-chairman.

By October of 2011, from community gardening to city planning, I had worked with a large number of incredible people working to improve the city and I felt excited about the future of Reading. Both the Rebuilding Reading Poverty Commission and Act 47 Community Committee had completed their work, some of which made it into the 2010 Act 47 recovery plan the City had to follow for the next five years.

By this point I had accomplished a lot, figuratively planting every seed of positive change I could in an effort of helping improve my hometown. But I was spread thin, and getting burnt out. When I get overwhelmed I tend to want to just work with my hands, and digging in the dirt is a proven way to do that. But the problems in the city grew worse. The month prior, Reading moved from the sixth to the first poorest city in the U.S. I couldn’t believe it, imagining places like Flint, MI, and Camden, NJ. This wasn’t how Reading, coming from a rich industrial history, should be remembered.

On November 8, 2011, Reading held its municipal elections, including the mayoral race. Candidate Spencer won, and became Mayor-Elect. I was appointed to the transition team, which as I learned is often a messy period involving a group of people in the candidate’s political circle scrambling to evaluate the situation she or he will be facing upon taking office, as well as jockeying for possible positions serving with the candidate, or even, apparantly, dealing with campaign donors inserting themselves in upcoming plans. At the center of all this was Mike Fleck and Samuel Ruchlewicz of Fleck Consulting. I had only met them in passing at this point, but it quickly became apparent that they were running the show.

Several weeks later I was asked to submit my resume for consideration in the new administration, so I could continue to serve Spencer as a policy adviser. I happily accepted the offer to serve that followed, imagining all the good I could do working within the Mayor’s Office. I had spent years in and out of governmental offices, both as an activist and consultant, so I believed I had a good idea of what to expect.

In reality, I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

PART 3: Working for Reading

I began working in my position as Special Assistant for Policy and Sustainability in the Office of the Mayor on January 3, 2012. My role was primarily focused on ensuring the Spencer Administration’s policy agenda and the Act 47 recovery plan were being executed. I did this by working with each of the departments in support their efforts towards meeting the administration’s goals. Joining me were Lawrence Murin, Special Assistant for Services and Workforce Development; Michael Dee, Special Assistant for Media and Communications; and Marisol Torres, Executive Assistant to the Mayor.

My overarching goal was to put Reading on the map in as many positive ways as possible. Preventing bankruptcy and emerging out of Act 47 were the primary objectives, but reversing our economic decline and poverty levels, and making the city more sustainable overall for the 21st century were urgent as well. Not only did I want Reading to improve, I dreamed of it becoming a model community others could learn from. But before I could work on all that, I technically had to get hired as a full-time employee.

Getting Off to a Bad Start

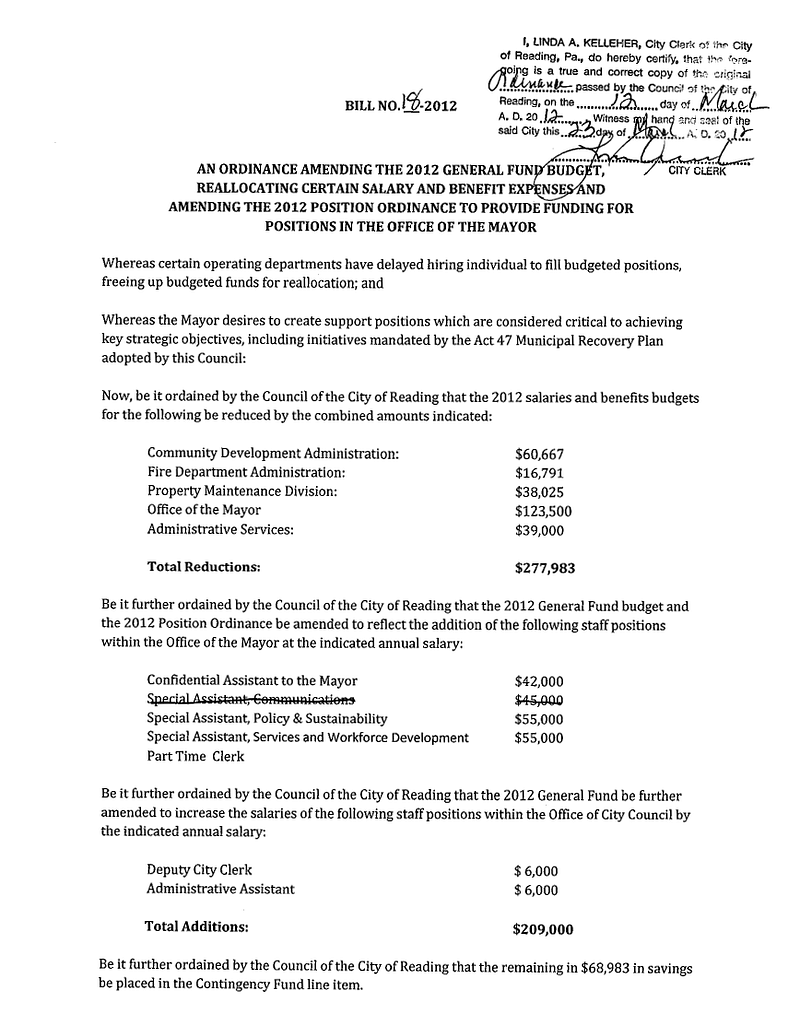

During the transition committee we worked on amending the FY 2012 budget to incorporate Spencer administration priorities, which included personnel changes. Because the recovery plan was already in place, any changes had to balance out to be approved, and negotiations with city council began before the new administration took office. Whatever state we assumed the negotiations were in, they fell apart at the first formal budget meeting and started the first of many disasters for the administration.

I do not have the space to recount the entire event, especially since that is not the key topic of my essay, so I’ll instead link to some of the Reading Eagle articles that covered it. In a nutshell, the administration and city council clashed over the new positions in the Office of the Mayor, which triggered a number of legal challenges and court battles that cost the City over a million dollars over several years. Experiencing that made me wonder if I could get anything done here.

Had this happened to me somewhere else — watching the organization I was just hired by fight for nearly two and a half months about my very position — I probably would have immediately looked for another job. But it being my hometown, I persisted, and on March 12, 2012, council finally approved an ordinance establishing my position.

So what changed to break the logjam? We can look at the way the ordinance was passed for clues. Bill 18–2012, which I’ve uploaded here, contains the details of the changes that were agreed upon to create my position.

In the bill, you’ll see three transactions. The first involved annual reductions from multiple administrative departments to free up funding for the Mayor’s Office positions. The second transaction creates the added expenditures for the Mayor’s Office positions. Given the backlash from members of council, as well as the newspaper, it appears that a fair compromise occurred. However, there is a third transaction that adds additional raises to Council Office staff. This was never discussed publicly, and essentially inserted as a last minute compromise without justification to seal the deal.

From my very first few months on the job, I was thrown into an environment of highly transactional political negotiations. Nearly every piece of political negotiations — especially legislation — goes through this “horse trading,” “wheeling and dealing,” or “what have you done for me lately” process. These terms have a sort of innocuous meaning to them, and you can call them what you want, but I’ve developed what I believe is a more accurate name for this process: a toxic culture of quid pro quo.

I believe things have a natural tendency to only get done in our governmental institutions through the reconciliation of a political ledger and at a high cost of time and money. And that’s true even when no one involved has a particularly malicious motivation. Thus, if even a minor corruptive influence is inserted into the process, the entire system can become overridden.

From that point forward, I had to look at things from this transactional perspective in order to move the ball forward. Playing the game of competing interests often led to a level of brinkmanship where winning was what mattered most. I do enjoy a good challenge mixed up with some worthy rivalry every now and then, but the sustained intensity of it at city hall was not what I wanted with the survival of the city at stake. I felt like we were our own worst enemy.

Sowing the Seeds of Destruction

Contributing heavily to the conflict was the presence of Fleck Consulting in city hall, having secured a contract with the City as paid municipal consultants. In the early weeks of the administration, they showed up almost daily; giving orders, holding meetings, and setting the schedule. Their demanding, demeaning, and disruptive style quickly poisoned the waters within city hall, so when I saw the opportunity to at least create some distance, I did. At the end of 2012 their contract was up for renewal, so I declined it, asserting that the campaign was over and the office staff must be in control of the administration’s agenda.

The conflict over influence then became the conflict over influence peddling. In 2013, even after their contract was over, I continued to get complaints that Fleck Consulting were constantly contacting city employees with requests for information or meetings with potential vendors. So I established a policy barring any campaign personnel from directly contacting municipal employees without prior authorization from the Mayor’s office.

This activity was happening at the very beginning of the transition, as I mentioned above, where one of the most vocal complaints I heard was regarding Fleck trying to insert so many individuals and organizations with ties to Allentown and Lehigh Valley in Reading politics. Candidate Spencer didn’t just bring Fleck Consulting in to win an election, but to emulate Allentown’s — along with Allentown’s Mayor Ed Pawlowski’s — growing success, and Fleck planned to capitalize on that to the fullest extent.

Looking back now, it’s clear that Mayor Spencer’s unwavering commitment to that goal via his relationship to Fleck would be the downfall of us all. With the multiple revitalization plans put together locally in the years leading up to 2012, why was Allentown so important?

A Tale of Two Cities

The cities of Allentown and Reading parallel each other in many ways. They both grew into vibrant industrial cities in early America that began declining by the mid-20th century. Both are located in the same Northeastern region of Pennsylvania, with similar size, demographics, and all other characteristics. Both entered the 21st century as part of the rustbelt of aging and distressed cities across the state. Within the last decade, however, as Reading continued into the direction of decline, Allentown began to rise, and many other cities were watching Allentown closely to replicate its success.

In 2012, the same year the Spencer Administration took office in Reading, Allentown was preparing to hit an inflection point. Up until then, the outlook in Allentown wasn’t much better than Reading, as summarized by Christopher Woods in Allentown’s Neighborhood Improvement Zone: Five Years of Failed Community and Economic Development:

Allentown, Pennsylvania, like many other mid-Atlantic industrial cities, was hit hard by the Great Recession. By 2012, a full four years after the generally recognized start of the recession, persons living below the poverty line, as a percentage of total population, soared 4.2 percentage points from pre-recession levels, unemployment was up 6.3 percentage points, and housing vacancy had increased by nearly 1,500 units (U.S. Census Bureau 2008–2012). For comparison, the national poverty rate increased only 2.7 percentage points, and the Pennsylvania poverty rate increased 1.6 percentage points over that same time (U.S. Census Bureau 2008–2012). Likewise, unemployment increased by 3.0 percentage points nationally and by 3.2 points in Pennsylvania (U.S. Census Bureau 2008–2012). In short, Allentown was particularly devastated in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

This inflection would begin in the coming year due to a change in Allentown’s tax policy initiated by the passage of PA Act 50 of 2009, sponsored by State Senator Pat Browne. This legislation created the Neighborhood Improvement Zone (NIZ), a unique tax zone similar to a tax incentive program called tax-increment financing (TIF). Woods describes the NIZ as

a one-of-a-kind tax subsidy that allows developers to capture state and local tax dollars to pay off the debts accrued in bonding to develop their commercial buildings within the 127 designated acres located in center-city Allentown and along the western side of the Lehigh River (ANIZDA 2017). These tax diversions pay down both interest and principal on the original loans. This subsidy allows developers to offer new commercial spaces at below-market prices (per square ft) because the costs of construction, and the costs of financing the buildings, are partially offset by tax diversions that will be generated once businesses begin to operate within the zone. The NIZ enables lower rents that incentivize large, established businesses to relocate into the zone. Sometimes, existing building owners deride the incentive because they struggle to compete with the artificially low rents (Harris 2019).

Although the NIZ legislation happened in 2009, the Great Recession suppressed redevelopment efforts everywhere, so visible activity in Allentown didn’t occur until 2012. When cities across Pennsylvania realized what was going on, and envy turned to anger when they realized the NIZ was exclusive to Allentown, state lawmakers drew up legislation for a statewide program modeled after the NIZ, named the City Revitalization and Improvement Zone (CRIZ). The cities of Reading, Lancaster, York, and more began the race to be awarded a CRIZ designation and attract the redevelopment being touted in Allentown.

This video showcases the kind of redevelopment in Allentown being sought out by Reading and many other cities across Pennsylvania through the use of CRIZ authorities. Video courtesy of Center City Allentown.

After mapping everything out to write this essay, I realized how important the role of the NIZ ended up being to the theme of corruption. I could write an essay of equal length to this one on my opinions of how NIZ-style economic development and the tax policy that fuels it is problematic in many ways, but these environments are acutely vulnerable to the corruption that redevelopment can attract. I don’t have enough information to show a clear line between Allentown’s redevelopment and the corruption that ensued in the following years, but it’s an important factor to consider.

One of the most interesting parallels between Reading and Allentown, to me at least, is that both cities share the exact same form of government: the Strong Mayor Home Rule model. In fact, they even share the same home rule charter: Reading established it in 1993, and Allentown adopted essentially the same one in 1996. I have always been a strong proponent of home rule, and still am to this day.

The important point in that, however, is the significance of the mayor’s role in both cities specifically chosen form of home rule government. During the legal conflicts early in my time at city hall, I developed a deep knowledge not just of Reading’s charter but of the theory of strong mayor system governing models. The mayor in this system, as a city’s chief executive, holds significant power. The theory argues that having an powerful individual at the head of municipal government can allow the city to better advocate and even fight for its interests unified behind an enabled leader.

The mayor of Allentown at the time of the NIZ-led redevelopment was Ed Pawlowski, in his second term as arguably the most popular mayor in the history of the city. Serving as head of a regional community development corporation and then Director of Community and Economic Development in Allentown before running for mayor in 2005, Pawlowski was instrumental in the city’s revitalization efforts. He was seen to many as a good model of a strong mayor.

In 2013, Mayor Pawlowski became president of the Pennsylvania Municipal League (PML), and won his third term as Mayor of Allentown. Buoyed by his achievements in Allentown and his involvement in the PML and other statewide and national initiatives, he announced a campaign to run for U.S. Senate in 2015, several months before the FBI raid on Allentown city hall.

A week after the raid, Pawlowski suspended his Senate campaign, but went on to win re-election on his fourth term as mayor in 2017 while under investigation. Swearing in as mayor again in January, 2018, he then resigned from office that March after being convicted of 47 counts of corruption charges, and ultimately was sentenced that October to 15 years in prison.

In Mayor Pawlowski’s case, the success of the NIZ, and the corruptive influences that followed, are linked to his downfall from the greed-fueled actions that grew within his campaign team. In this WFMZ article covering court testimony during Pawlowski’s trial, you can sense the cognitive dissonance that seemed to exist in the mayor’s mind between his thoughts and his actions while talking to Mike Fleck during a wiretapped recording.

Since taking office, Mayor Spencer would often look to see how Mayor Pawlowski was handling things, either for inspiration or even emulation. Leading cities with many of the same issues, from gun violence to homelessness, they were both involved in many of the same initiatives. To Mayor Spencer, Mayor Pawlowski had a winning playbook that he also intended to follow. A big problem, of course, were the political consultants they both hired to grow their success, and their own failures to stop what had started. And in both cases, they reaped what they sowed.

Something’s Rotten in Reading

Getting back to Reading, while the legal battles with the Charter Board continued, yet another legal issue surfaced in the November of 2013. The Berks County Board of Elections released the report of an investigation into a $30,000 contribution to Candidate Spencer’s 2011 campaign from IBEW Local 98. The investigation alleged that the Spencer campaign improperly used the funds to channel money back to several Philadelphia council candidates. I was told by both Spencer and Fleck Consulting that it was a witch hunt and was reassured that it was being addressed.

I never quite bought the story, but there were lawyers from both Spencer and the campaign consultants involved, so I trusted it was true. I think the fact that we kept winning legal fights gave me a false sense of security that Mayor Spencer’s political consultants did know what they were doing, and maybe I was wrong to continue challenging them. Battle fatigue had really settled in.

Almost two years into the term, I tried to stay focused on doing my job instead of stressing over these issues. In situations like this, however, that’s not a good strategy. I only started digging a hole.

Holding up a House of Cards

I slowly realized how much of my time was being spent on political problems, and my ability to focus on my policy work during the day diminished. Nights and weekends are when I generally did what I was hired to do, but some days I’d be so worn out that I came home and just crashed. Those nights I would watch shows like West Wing and House of Cards, where the political drama was always center stage, and the people around the main characters — particularly the Chief of Staff — were always cleaning up the mess.

I, too, came to see myself as a fixer, regardless if it was my job or not, because I believed my duty was to make the mayor and the administration, and thus the city, successful. Thanks to my personal efforts through my therapist, I came to grips with some of my behavioral tendencies — most bad, but even some of my best qualities — that contributed to the tunnel vision I developed in city hall:

- I’m a textbook workaholic, something I have to manage as a real addiction to this day. The consequences of this should be obvious, but one of the main things it did was begin to exhaust my energy, wearing down my will to fight. More on this below.

- I suffered from generalized anxiety disorder, which wasn’t being treated properly in any way. Anxiety can create fuel for a workaholic to maintain their overdrive, and my job gave me plenty to stress over.

- I’m very stoic, which while having it’s advantages, suppresses important emotions designed to safeguard our well-being. I trudged ahead through a lot of bullshit that should have convinced me to find another job. More on that later, too.

- I enjoy being in positions where I can take advantage of my range as a master generalist. I have a tendency, as I’ve observed even since city hall, to quickly develop an understanding and then involvement in all aspects of an organization’s activities. That’s a real asset in a healthy culture, but dangerous in a toxic one, especially if you aren’t very self-aware.

Adding to this, I was incredibly invested in just making things happen, overall. From my personal work in college, to the Act 47 and anti-poverty plans, and now the Spencer platform, I became so mission-driven that my focus was on eliminating any obstacle to success.

Being immersed in this mindset every day creates that tunnel vision and, over time, an “ends justify the means” attitude. Talking with my family or friends, even when complaining about the amount of bullshit I constantly had to deal with, I began rationalizing it away — as a stoic often would — as “just the way it is.” In a political environment, with corruptive influences all around, this is a very dangerous attitude.

For the next two years, I continued to dig the hole.

Critical Lapses in Leadership

I’d like to preface this section by saying that despite everything that happened, I do believe that Vaughn Spencer is a good person, had many good intentions throughout his political career, and outside of this essay’s context, truly worked as a dedicated public servant.

We developed a close bond through our time together, and shared many of the same goals and values. This was a key reason I chose to serve under him in the first place. However, good people do not by default make good leaders, and this was unfortunately the case with Mayor Spencer.

In many municipalities, the mayor is mainly a figurehead, serving a ceremonial role at public meetings and events, and whose main power is vetoing legislation. Reading, however, adopted a strong mayor form of government, which puts significant demands on the mayor as a chief executive.

Although Mayor Spencer believed in, and even fought for, the Strong Mayor doctrine, he was unable to perform that role. I believe this weakness was a key cause of many failures of the Spencer administration, including allowing corruption to occupy the mayor’s office.

Every group of people, particularly when they begin working together for a prolonged period of time, go through a set of stages as they feel out their roles, display their personalities, and attempt to get things done. Commonly know as “forming, storming, norming, and performing,” these are Tuckman’s stages of group development. Reading city hall has a long-standing reputation of friction and conflict, so rising tensions within the Spencer administration’s leadership team was inevitable.

With the mayor’s office getting off to a rough start, and the disruptive presence of the political consultants, there wasn’t time spent on truly building trust within the leadership team, which included the staff of the mayor’s office, managing director’s office, and the heads of all the departments and divisions of the administration. Things like this naturally take time, so I did my best to facilitate cohesion within the group.

By the Spring of 2014, however, things had not yet improved to the “norming” phase, and I realized that in many cases, Mayor Spencer was a common denominator in disputes. This was especially true in the dynamics between the offices of the mayor and managing director, where miscommunication, mistrust, and often conflicting views on what Mayor Spencer wanted done created clashes.

I organized multiple mediation sessions to work through the conflict, but when it became apparent that Mayor Spencer had to step up and give better direction, he wasn’t able to. He was a people-pleaser that preferred to avoid conflict, when possible, and would use ambiguity if it would smooth things over or buy him time.

While this weakness was a problem for team dynamics within the administration, nowhere did this weakness have greater consequences than in Mayor Spencer’s decision to continue to retain Fleck Consulting. In what should have been a warning sign, his failure to properly confront this critical issue caused Mayor Spencer to lose several of his closest allies: Lawrence Murin, special assistant in the mayor’s office, and Greg Walker, treasurer of Friends of Vaughn Spencer.

Around the same time as the mediation work, Lawrence and I were trying to find replacement consultants for Spencer’s re-election campaign. We met with key local activists and tried to set up calls with their referred contacts, but Mayor Spencer kept declining. The combined failure of Mayor Spencer’s inability to lead through the staff conflicts and refusal to fire Fleck Consulting caused Lawrence to resign in protest. Lawrence encouraged me to resign with him, but I decided to stay on and find a way to solve these problems — well-entrenched in my fixer role by this point. I still regret my decision not to resign with Lawrence to this day.

In the Summer of 2014, it was reported that the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office was continuing the 2012–13 investigation into possible campaign contribution violations by the 2011 Spencer campaign. This revelation, as well as the fact that Fleck Consulting would remain under contract for the re-election, caused Greg Walker, Spencer’s campaign treasurer and a close childhood friend, to resign in protest as well. When no one else would volunteer as treasurer, I offered to do it in classic fixer fashion — thinking I could somehow use the purse strings to reign Fleck Consulting in. This too, of course, is another decision I still regret to this day.

That Fall Mayor Spencer and I met with Fleck Consulting to formalize re-election plans. By that point I was resigned to the fact that Mayor Spencer wouldn’t remove them, and hoped I could somehow control things. They explained that Fleck Consulting merged with Seven Points Consulting to handle campaign consulting and lobbying work was split off into Hamilton Development Partners, allegedly to prevent conflicts of interest. In addition, the PA Attorney General’s office apparently dropped their investigation of the 2011 campaign contributions from IBEW-98, without explanation.

These developments gave me a false sense of assurance that everything would be above board, and that perhaps I was overreacting. I still was not happy to be working with them again, but I had to put my faith in Spencer, and trusted he would hold the line.

The Election and the Aftermath

Before covering the 2015 primary election, I believe it’s important to begin with a short backstory.

After being elected to City Council in 2001, then-Council President Spencer attempted to run for mayor twice, in 2003 and 2007, and lost twice. It was a position he wanted for a long time. In 2011, when Mayor McMahon announced he was not running for a third term, Council President Spencer entered the race again.

From what I remember, Fleck Consulting had recently begun marketing their services outside of Lehigh Valley at this point, and Council President Spencer was introduced to them. Seeing their success in Allentown, as I covered above, he brought them on to run his 2011 mayoral campaign.

I was not a formal member of the campaign during the 2011 primary race, but I knew several people who were, and they complained about their treatment from Fleck Consulting. Yet Candidate Spencer won the primary with their help, and went on to win the general election, as well. Mayor-Elect Spencer continued crediting them for winning the race, giving them the kingmaker status and privilege that comes along with it they were after.

Between the fateful meeting in 2011 through the end of 2014, there was a clear pattern of problematic interactions involving the political consultants, and despite the efforts of myself, Lawrence Murin, Greg Walker, and many others, Mayor Spencer insisted they stay. There is a quote of unknown origin that says “what you allow is what will continue,” and that is exactly what happened from that point forward.

But it wasn’t just Spencer’s decisions that contributed to our collective downfall; I bear responsibility as well. After six years of reflection and replaying the events of 2015, I can now confidently and publicly speak of the three fatal mistakes I made. All three were tied to campaign money and the culture of corruption that was allowed to continue, and continue it did.

On January 15th, 2015, the campaign for Spencer’s re-election officially kicked off, again with Mike Fleck in control of the show. Mayor Spencer was making fundraising calls nearly every day, and the consultants were spending money as fast as the campaign received it. When the mayor could avoid it, he would duck out of meeting with donors and have me meet them instead. Somehow I thought that was better, as I often dealt with matters Mayor Spencer chose to avoid. This was my first fatal mistake.

Two months later, that March, we had realized a campaign contribution amendment to the City’s Ethics Code was in effect that election, and four mayoral candidates, including Mayor Spencer, violated the new limits. The Reading Eagle was absolutely right that it was the responsibility of each campaign to know and abide by all rules, but there were substantive issues with the ordinance and its implementation as well. I raised the issue, and worked to repeal it for what I believed were valid reasons, but the quid pro quo methods that resulted were absolutely wrong. This was my second fatal mistake.

Several weeks later, now knowing the campaign limits were in place and campaign spending continuing at an alarming rate, I raised my concerns as treasurer to Mayor Spencer. The mayor then called Mike Fleck, and I confronted him about the spending. He exploded over the phone, reminding me that I kicked him out of the mayor’s office, and that we run city hall and he runs that campaign, or he’s walking. “It’s either Eron or me, Vaughn,” he threatened the mayor, who tried to smooth everything over before I responded. Ending the call, Mayor Spencer just looked at me, shook his head, and said “they know how to win.” It was at that very moment that I went completely numb.

I should have resigned on the spot, but instead I just shut down. All fight in me was gone. I began telling myself that the campaign was almost over, and to just keep my head down and stay out of the way. I believed that after the primary I could get rid of these campaign consultants for good, and everything would be better in the second term. But I was just a fool, and by staying on I buried myself in the hole I’d been digging this entire time. That was my third fatal mistake.

On election night, as the the poll returns were nearing completion, I realized we had lost by a landslide. I believed it would be close, but it wasn’t even. Mayor-Elect Wally Scott won by a 3:1 margin over Mayor Spencer. I was stunned at the result, trying to figure out what went wrong. But then I realized it really didn’t matter at that point; we lost, it was over, and thinking of all my struggles, maybe that was best.

In the weeks after the election and before the FBI raid, I believed I still wanted a future in government. I thought I could recover my personal work and find a way to move on. If things had been different, that’s probably what would have happened. But I’m actually glad it didn’t, because I was still contaminated by corruption and could have sunk much deeper into that culture in another place.

The rest, at that point, is literally history, but certainly not the history I wanted to make. In always trying to “win” everything we faced, lines were blurred in the beginning, and thickened into a fog of war in the end. Yet we still lost, and at a tremendous cost to ourselves and very community we originally were fighting for. But it wasn’t just the election that we lost. Along the way in the pursuit of winning, we lost our moral compass and ethical guardrails, due to the allowance of a corruptive influence in our work.

Mayor Spencer was fond of the following passage in a speech by President Theodore Roosevelt, entitled Citizen in the Republic, which he would cite regularly:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

And at end of Mayor Spencer’s time in the arena, he failed while daring greatly, but not for the right risks. He was convicted by a jury on August 30, 2018, and on April 24, 2019, he was sentenced to eight years in prison. In the Morning Call article for that day, by Peter Hall, we learn about some of the interactions during his sentencing:

“Vaughn Spencer had great potential,” [First Asst. U.S. Attorney Jennifer Arbittier-Williams] said. “He was a public school teacher who was elected mayor and he had the ability to do such good, but he squandered that because of greed and ambition, and now he’s going away to prison for eight years.”

Hall reports that Mayor Spencer expressed remorse but couldn’t justify why he allowed the corruption to continue:

The judge also questioned Spencer about his decision to keep working with Fleck and Ruchlewicz even after his assistant, Lloyd, “rang the bell for you loud and clear” to stay away from pay-to-play … [to which] Spencer on Wednesday told the judge he kept Fleck on his team because he felt it was improper to run a campaign himself while he was responsible for running the city.

What was improper, obviously, was the inverse — but Mayor Spencer never could see the truth. Towards the end of his questioning, Hall recounts, he apologized for what he put me and other staff through, which I appreciate:

Spencer said it stung to hear his employees at trial say they feared he would fire them, noting that he tried to instill a spirit of camaraderie at City Hall, with Reading Phillies outings and Christmas parties paid for from his own pocket. … He singled out his special assistant Eron Lloyd, who pleaded guilty in a bribery scheme to repeal local campaign contributions and was sentenced to probation, as a bright young man whom Spencer never intended to pressure.

I forgave Vaughn Spencer for what he put me through, and hold no grudge against him. It is easy to fall into that gladiator mindset, to be completely focused on victory, and simply fight your way through everything in your path. This was the trap the mayor fell into.

In the arena, however, you must always remember that what you fight for and how you win matters, too. If you forget this, or even reject this, you allow corruption in the arena, and inevitably, defeat. For if allowed to continue, corruption will always win in the end.

The Insight from My Hindsight

As I close out this chapter of my life, having reflected on what happened, there is a common pattern throughout the story of failing to heed the many warning signs of what was happening, and then do something about it. I developed a blind spot that slowly spread until I became nearly blind. I’ve talked above about the many times I stayed silent, looked away, played along, or shut down entirely. In doing so, I slowly closed my eyes to corruption. And then I failed.

My failure was a very costly and public one that I’ll have to carry with me for the rest of my life, continually revisiting it as necessary before people with the power to pass judgement on me in the context of my criminal record. I can live with that, having full confidence in my true character and resilient nature.

But what I can’t live with is the thought that this problem will continue to persist. When political, business, or religious leaders are prosecuted for corruption, language such as “corruption has been rooted out of our city” is often used, as if removing individuals is enough to stop the spread. We attribute corruption to those indicted, and then carry on believing the problem had been carved out. Until it happens again, in a different time, and with different people, but often the same ways and always for the same reasons: money and power.

Corruption will continue until we see the problem for what it is, and solve it in ways to stop it for good. I want my personal story to help others keep their eyes wide open, and hopefully do something about it. That begins with awareness, and there are two actions I urge both individuals and organizations to commit to:

- For organizations of all shapes and sizes, public and private, provide and require training of an officially adopted code of ethics, and specifically call out behaviors associated with bribery and fraud as zero tolerance offenses. Transparency International provides anti-corruption toolkits for all segments of society to build their program on.

- For individuals, ensure you are trained and fully aware of your organization’s code of ethics, including how to safely report violations. As soon as you sense something is wrong, stand up, speak out, push back, and if you aren’t being heard, walk out. Nothing you think you’re doing in an organization is worth the risk of compromising your values and ethics or breaking the law. In the end, you’ll only allow your values and ethics to be compromised.

As for me, although that chapter is now over, my story is not. I entered politics as a reformer, and I have returned to my roots as a reformer of politics, beginning with corruption. I will continue to write about my efforts moving forward, for those interested. And if you have read this far, I thank you immensely for your interest in my experience, and hope you’ll join me in the fight for our collective future.

I originally planned to end my essay here, but after the extensive research I did exploring the roots of corruption and what can be done about it, I decided to add a forth part to further contribute to the cause. If you, too, agree that corruption must not continue, and are ready to get involved, I urge you to read ahead.

PART 4: True Change Must Begin with the System

“If we put corrupt men in public office and sneeringly acquiesce in their corruptions, then we are wrong ourselves.”

— Theodore Roosevelt

Six years ago, as I was getting my life back on track, I committed to also start educating myself on the problem of corruption like I would any other policy challenge I’ve focused on in the past. Like most people, I previously held a generally one-dimensional view of corruption, colored by images of organized crime, crooked politicians or police officers, and unchecked corporate greed. And in most instances, as I discussed above, the focus was on corrupted individuals or groups of people.

After being charged and pleading guilty to bribery myself, of course one of the first thoughts going through my head was “does this make me a bad person?” Following my plea hearing, I was admittedly angry for a short time: angry at myself, angry at Vaughn Spencer, angry at the consultants, Reading, the system, everything. I guess it only seems natural at this point to react that way when you screw up your life.

Then the denial set in. One of the first things I came across was an article reviewing a provocatively titled book, Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent. I still haven’t read the book, but the author makes some interesting arguments about issues around the prosecution of actions where either intent is questionable or the action may not actually be illegal.

I also stumbled across a Twitter account listing ridiculous federal laws that anyone could accidentally break, risking criminal charges. Apparently since then the Twitter account author released a full book of this content, which I probably will read. Finding these resources briefly made me feel better; someone could face the same problems I did by violating the ubiquitous FBI warnings before every movie, in fact!

But I quickly sobered up and accepted my reality. To be clear, I violated a portion of 18 USC Section 371. Regardless of my intent, it was wrong, and the law was well-defined in my case. My question of “was I a bad person because I did a bad thing?” lingered for years to come, despite my research. Fortunately I came across the right books just as I worked up the courage to crack open my personal archives and write this essay, and it’s been illuminating.

I know I’m a good person. At night I sleep well, free of the shame I carried with me for years, and when I look in the mirror I see the same person I’ve always been, but a bit wiser, and a bit stronger. My actions and reputation both before and after my ethical lapse during my time in the Spencer administration demonstrate this. My therapist validates this, as well as everyone that knows me.

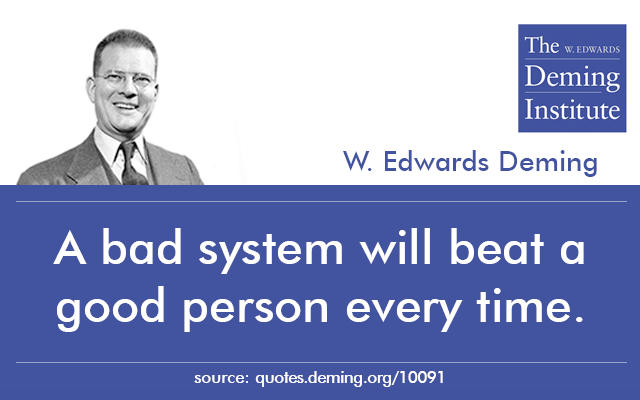

But it still troubled me to think about how everything happened, and how the same thing could happen to anyone else in similar circumstances. I had to remove my personal feelings from the issue and approach it as I would any other complex problem — with systems thinking. It has to be a bad system, I believed, but I needed to prove this to myself to truly be at peace. And as it turns out, I was correct. Here’s what I found.

Does Power Corrupt?

Every time someone in a leadership role is charged with corruption, you’ll inevitably hear someone else cynically shake their head and mutter “Well, power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” In my short but intense career in politics, I’ve heard people with power direct that to other people in power, in the same manner politicians often accuse each other of “playing politics.”

To me it felt more like a hollow cliché, targeted at specific powerful people and not a broad critique, yet beneath the cynical superficiality lies a more profound statement with a real history. In Dr. Brian Klaas’ book Corruptible: Who Gets Power and How it Changes Us, I learned that the quote originated in a letter from John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton (Lord Acton) to Archbishop Mandell Creighton in 1887:

I cannot accept your canon that we are to judge Pope and King unlike other men, with a favorable presumption that they did no wrong. If there is any presumption it is the other way against holders of power, increasing as the power increases. Historic responsibility [that is, the later judgment of historians] has to make up for the want of legal responsibility [that is, legal consequences during the rulers’ lifetimes]. Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority: still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority. There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it.

The statement, as is often the case, is so much more substantive in its original context. Through stories like that of Lord Acton’s above, Dr. Brian Klaas, a professor of global politics at University College London, sought out to answer four questions related to this quote:

- Do worse people get power?

- Why do we let people control us who clearly have no business being in control?

- Does power make people worse?

- How can we ensure that incorruptible people get into power and wield it justly?

I highly recommend you read the full book, but for the purpose of this section, I’ll quickly summarize some of the findings in the book that help to answer these questions.